After an initial liking of his work, last year found me fully appreciating Stanley Spencer's idiosyncratic and uplifting art largely due to his inclusion in the wonderful exhibition CRISIS OF BRILLIANCE which set him within the context of his Slade art school contemporaries.

Earlier this year we saw the equally amazing exhibition at Somerset House of the site-specific WWI canvasses he painted for the Sandham Memorial Chapel so a week ago we decided to journey north-west to the commuter town of Cookham in Berkshire to visit the Stanley Spencer Museum, a few doors along the high street from the house where he was born.

The museum is in a converted Wesleyan hall where Spencer attended meetings in his youth and there is even a drawing in the museum from around 1937 called "Ecstasy in a Wesleyan Chapel" of a congregation getting the spirit. It's a very odd experience to look at it in the very space that he was inspired by.

It's a bright airy hall with nothing to distract you from the paintings on display. The museum seems to have different exhibitions twice a year and when we visited they were showing PARADISE REGAINED: Stanley Spencer In The Aftermath Of WWI, which ties in nicely with the centenary of WWI this year.

The War came two years after Spencer left the Slade and initially he resisted the call to sign up as he was establishing his career but the sight of his generation returning to the town from the front made him decide to join the Medical Corps. and after training in Bristol, he served in Macedonia. The happiness of returning at the end of the War was tempered by the death of his brother Sydney two months before the armistice.

His experiences in wartime and the return to his birthplace are reflected in his work, none more so than in his 1922 painting "Unveiling Cookham's War Memorial" which we had seen in the CRISIS OF BRILLIANCE show. His busy canvas, teaming with life and good humour, shows the memorial seconds after the unveiling with the rows of onlookers crowding around. It is interesting that the ones least interested are the young men who lounge on the green, ignoring the hub-bub, no doubt glad to be rid of the War as they were the ones who had to risk their lives. Schoolboys misbehave with the schoolgirls dressed in white that stand before them while one girl moves the flag aside to find which name? - Father? Brother? Both?

After leaving the Museum we walked back up through the town and there was the Memorial, a bit more built up from that day in 1919 that Spencer immortalised three years later. Indeed the wooded hills seen in his painting are now hidden by a very nice pub where we had our lunch! Easily found among the memorial names is Stanley's brother Sidney, seen in the picture above, standing with Stanley beside their seated brother, Percy. Stanley's clean-shaven and slightly wary gaze is also echoed in his excellent self-portrait in the museum from 1914.

Along with his allegorical paintings which are usually set around and about Cookham, the Museum also boasts a huge unfinished work called "Christ Preaching At Cookham Regatta" (1952-59) with Christ seated in a punt addressing the crowds on the bank of the Thames. Spencer struggled to complete the work - a search for a sponser for the painting proved fruitless - and it is fascinating to see what he completed and what he left for another day which sadly never arrived. Another delight were his paintings of trees and shrubs growing around houses in the area.

This small, delightful Museum also deserves high praise for it's well-illustrated and detailed exhibition catalogue as well as an extensive postcard selection - for once a Museum that knows what the public really wants!

I am looking forward to another visit when there is a new theme explored in this extraordinary but ordinary artist's life and work.

In 1941, after establishing himself as one of the most groundbreaking 20th Century artists, Henri Matisse was felled by the third of three momentous events. In 1939, as well as the outbreak of the 2nd World War, Matisse had a bitter separation from his wife of over 40 years and now he had become incapacitated by an intestinal operation which even his doctors thought would extend his life by only three years.

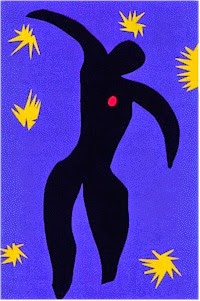

Confined to his bed or a wheelchair, Matisse's urge to create burned as strong as ever and he utilised a technique that he had previously only used while preparing earlier paintings: he had used rough cut-out shapes to pin on his canvas and move around until happy with the composition of colours. Why not just use the cut-outs now?

In 1947, he completed JAZZ a large book which included his cut-outs alongside his writings on them. In the exhibition you can contrast the printed versions with the original designs and I knew exactly how Matisse felt when he saw the finished work, yes the designs stand out from the page due to their stark modernity but the sheer vibrancy of the colours are lost in the printing process.

It's hard to believe that Tate Modern has come up with another show to match their PAUL KLEE earlier this year but this too is a glorious exhibition. Luckily we went to one of the Saturday late-night openings and while busy it was not crowded so it was easy to walk around and enjoy the cut-outs at leisure.

There were so many works to treasure: OCEANA, the underwater cut-out murals that Matisse covered his living room walls with as well as works from his studio which leap out and dazzle due to the colour combinations - sadly we do not experience them as Matisse and his helpers did as he pinned them loosely to the wall so they would undulate in the breeze.

There is a room dedicated to his work designing the Dominican Chapel of the Rosary in Vence. He did it as a gesture of thanks to Monique Bourgeois, a young nurse who had helped Matisse recover from his 1941 operation and who had become a Dominican nun in 1946. They maintained a friendship and when she asked him to design a window for her chapel, he instead took over the design of the whole interior, even down to the priest's vestments.

There is also a lovely work called The Bees that dazzles the eye with it's vibrant colour and modernist design. Again, as with the Paul Klee exhibition, I was reminded of Seurat's thoughts of the harmony that can happen when the two right colours are placed together and THE BEES is a true harmony of colour and movement.

Then there are the works using just one colour such as the Blue Nudes which need to be seen "in the paper" where instead of just flat colour, you can see where Matisse added different pieces of paper built up to give the figures a real texture. Also it is telling to recall that while he was creating these images of flowing, intricate, plastic movement he himself was increasingly frail and confined to his bed or chair.

The exhibition then has increasingly larger works - vast wall-size designs which again dazzle with the simplicity of the vision - until we reach their apotheosis, the massive work from 1953 THE SNAIL.

All his years of fauvism, post-modernism, his explorations into colour and into abstractionism have led him to this wonderful distillation of his vision. It's fascinating to contemplate and also to observe up close, most of the large blocks of coloured paper have smooth edges while some are torn - you can almost see him tearing through the paper with his large scissors - and to see the tiny pinholes in the paper where his assistants have moved them to *just* the right place.

I was involved in a convoluted debate in an art class a few years ago over this painting, one guy simply refusing to give himself over to it and repeating "But why is it called The Snail"? Because the man in the wheelchair says it is... that's good enough for me.

The year after completing THE SNAIL, Matisse suffered a heart attack, dying three days later aged 84.

Matisse said "By creating these coloured paper cut-outs, it seems to me that I am happily anticipating things to come. I don't think that I have ever found such balance as I have in creating these paper cut-outs. But I know that it will only be much later that people will realise to what extent the work I am doing today is in step with the future."

The cut-outs are not only ageless but they pulse with the energy and life of their creator. A life-long atheist, he said he only believed in God when he worked. Oddly enough, I only believe in God when I see his work and those of any artist of true vision.

1 comment:

Thanks for the tour! Matisse is a favorite and you've brought some of the best to my living room.

Post a Comment